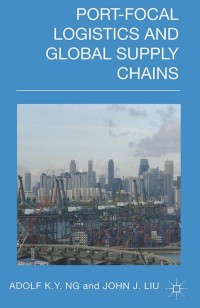

Book

Port-Focal Logistics and Global Supply Chains

This book explores the intersection of two trends in the port sector that have occupied researchers in recent years: the port's progressively interventionist role in the hinterland and its increasing importance as a node within supply chains. These trends are set against the backdrop of fierce port competition as the increasing size of modern container vessels drives ports to make huge investments to retain their connections.

The conceptual approach is derived from a sound reading of the literature, in which the hinterland has become one of the key battle- grounds for port authorities and terminal operators. As the sea leg has become increasingly cost effective due to the deployment of large vessels resulting in concentration of traffic flows at major hubs, the inland leg remains challenging from both practical and organisational perspectives. Thus, streamlining hinterland transport, whether through infrastructure investment or organisational collaboration, has become a major topic within maritime research during the last decade. The interdisciplinary collaboration between specialists in maritime geography and supply chain management (Liu) suggests an innovative approach to this topic, as the study of freight transport is increasingly difficult to separate from its context within logistics and indeed its wider situation within the field of supply chain management.

More specifically, the book seeks to explore a somewhat contentious point among scholars in maritime logistics, regarding whether inland locations (inland terminals, dry ports, etc.) are more suitable than within or nearby the port (sometimes called “port-centric”) for logistics operations. The rise of containerization and more integrated supply chains, in tandem with economies of scale available from high capacity inter modal corridors, has, at least in some parts of the world, led to an increase in containerized goods moving smoothly through ports to distant hinterlands for stripping and processing (and vice versa for exports). On the other hand, certain factors encourage emptying containers within or near the port and even locating the full distribution operation at a port location. By introducing their “port-focal” concept, the authors hope to synthesise the two approaches and unlock their complementary. They state that “port-focal logistics can thus be understood as an integrated logistical system supported by the effective operation and governance of interrelated logistics hubs (ports)” (p. 205).

Empirical material based on fieldwork undertaken by the authors is utilized throughout the book. The port logistics chapter discusses the case of Hong Kong, while the chapter on institutions compares case studies of Busan and Rotterdam. The major empirical content, however, is presented in two indepth case study chapters on India and Brazil. The analysis explores what the authors term the “environmental heterogeneity” produced by the institutional and bureaucratic factors that are crucial requirements for the successful development of dry ports. The authors question the extent to which generic solutions from Western countries are applicable to non-Western countries. In this perspective, the authors' concern with environmental heterogeneity is an important consideration underpinning global comparisons and development expectations. While as scholars we generally seek to find underlying frameworks and generic models that describe phenomena in all contexts, it could also be argued that too few studies explore the global political and geo-economic context of transport, as though all countries are expected to converge upon the same neoliberal development paradigm (cf. Fukuyama (1992) and the “end of history”).

The authors argue that, while container ports share a similar asset specificity, the diversity of governance structures observed derives from their operational context of environmental heterogeneity. Thus, one of the key characteristics of port-focal logistics is that “port production is faced with idiosyncratic demands from the oligopolistic shipping market, while firm production is assumed to face systematic demands from a competitive market” (p. 54).

Ultimately, the book is a plea for more integrated and coordinated supply chains to benefit the network as a whole rather than destructive competition between individual firms. The authors argue that focusing on the port as the key node through which many supply chains pass makes port actors best placed to coordinate this process. Few would argue that supply chains are becoming more integrated due partly to the need to obtain economies of scale and scope but also due to the need for information sharing to improve responsiveness and flexibility within supply chains that span the globe. The question is whether the role of the port in this supply chain is now the determinative aspect. Do all or most ports have the ability and indeed interest to integrate processes within the supply chains of their customers? Moreover, do their customers agree? More interdisciplinary work is required in order to advance understanding of these important questions. Thinking along these lines, a suggestion for further research might be to move beyond resources to relationships. Such an approach might consider applying the relational view of resources, in which assets are viewed as relation- ship specific rather than firm specific. Port scholars in general as well as geographers require a deeper understanding of logistics and supply chain management in order to construct a joint conceptualization of where geography and economics intersect in the market positioning of ports.

Ketersediaan

Informasi Detail

- Judul Seri

-

-

- No. Panggil

-

TXT PO ADO p

- Penerbit

- United Kingdom : Palgrave Macmillan., 2014

- Deskripsi Fisik

-

-

- Bahasa

-

Indonesia

- ISBN/ISSN

-

978-1-349-44539-4

- Klasifikasi

-

Po

- Tipe Isi

-

-

- Tipe Media

-

-

- Tipe Pembawa

-

-

- Edisi

-

-

- Subjek

- Info Detail Spesifik

-

-

- Pernyataan Tanggungjawab

-

Adolf K. Y. Ng

Versi lain/terkait

| Judul | Edisi | Bahasa |

|---|---|---|

| Global logistics : new directions in supply chain management | Fifth Ed. | en |

| Review Of Maritime Transport 2014 | en |

Lampiran Berkas

Komentar

Anda harus masuk sebelum memberikan komentar

Karya Umum

Karya Umum  Filsafat

Filsafat  Agama

Agama  Ilmu-ilmu Sosial

Ilmu-ilmu Sosial  Bahasa

Bahasa  Ilmu-ilmu Murni

Ilmu-ilmu Murni  Ilmu-ilmu Terapan

Ilmu-ilmu Terapan  Kesenian, Hiburan, dan Olahraga

Kesenian, Hiburan, dan Olahraga  Kesusastraan

Kesusastraan  Geografi dan Sejarah

Geografi dan Sejarah